In the last blog, we began to explore the interesting (and relevant) question of how we should understand the forceful conquest of the land of Canaan by the ancient Israelites as recorded in the Old Testament books of Joshua and Judges. God was settling the new nation of Israel in Canaan, and this new nation consisted not only of the now-freed Semitic slaves from Egypt but also other racial groups escaping Egypt, who also combined with the marginalized and oppressed people within Canaan. God made a “covenant” with this new nation to bless them if they would pledge their love and allegiance to him. God intended for the nation of Israel to be different (“holy”) from the other nations in Canaan. The nations in Canaan were much like ancient Egypt–aggressive, violent, greedy and power-hungry. Israel, on the other hand, was to be known for its “love of neighbor” (which included the foreigners among them), its concern for the poor, and its culture of forgiveness, honesty and integrity (read the book of Deuteronomy to get a glimpse of the character of God). In other words, Israel was supposed to reflect the loving character of its God. By their allegiance, trust and obedience to God, the Israelites would be a light to the nations, transforming its culture. So what did Israel do? Let’s look at what God told them to do, and then what they did.

“Destroy the Alters and Cut Down the Asherah Poles”

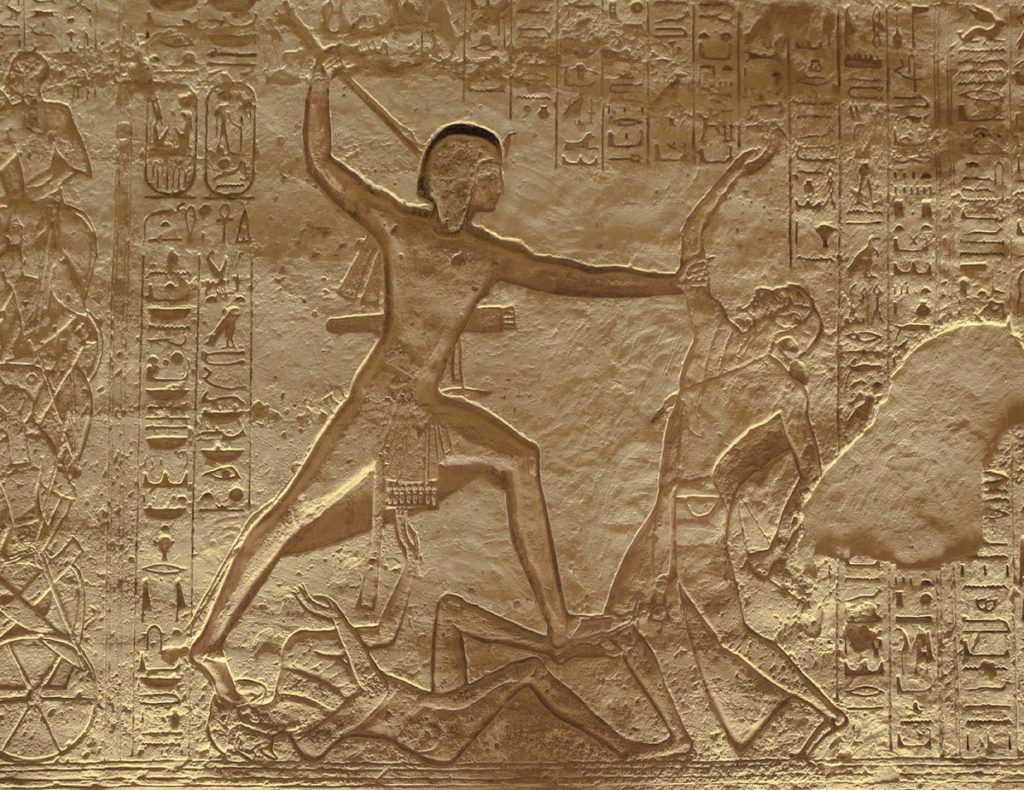

Settling in Canaan was not going to be easy, not only because the Canaanite city-states did not want to give up any land to foreigners moving in but also because the differences between the God of Israel and the gods of the Canaanites couldn’t be greater. The battle was a battle of worldviews, a battle of the gods, a battle for the hearts of the people in deciding which god they would choose. The Israelites, formed under the benevolent kingship of Yahweh (the God of Israel), would be a striking contrast with the city-states of Canaan, a culture where power and survival were paramount. Instead of believing in a God of the whole world whose character was one of compassion and truth, the powerful among the Canaanites formed gods of their imaginations. Because power and survival were critical to the Canaanites, each city-state had its own particular “god” that would fight the gods of other city-states. God was manipulated to serve the purposes of the powerful.

Before entering Canaan, Moses and Joshua warned the Israelites not to assimilate the “gods” of the Canaanites nor “bow down” or “serve” those gods. If they did, the gods would become “a snare and a trap for you, a whip on your sides and thorns in your eyes, until you perish from off this good ground that Yahweh your God has given you” (Joshua 23:13). As they entered Canaan, the Israelites were to “break down their alters, smash their sacred stones and cut down their Asherah poles.[1] Do not worship any other god, for Yahweh, whose name is Passionate, is a jealous God” (Ex. 34:13)[2]. The Israelites were not to adopt this power-hungry culture of the Canaanites, but were to destroy all the religious practices and paraphernalia that the Canaanite dictators used to keep control over the people. The Israelites were also prohibited from profiting from any of the plunder from the key city-states they overcame, but were to “devote to destruction” the key city-states and their worship places (for an insightful description of what Israel was supposed to do, read Deuteronomy 12). At the heart of the Israelites’ conquest of these Canaanite city-states is the destruction of Canaan’s oppressive power structure. As Christopher Wright points out, “The conquest of Canaan, as a unique and limited historical event, was never meant to become a model for how all future generations were to behave toward their contemporary enemies.”[3]

What Israel Chose

The book of Judges begins with some successes in fighting against the city-states in Canaan. With such an auspicious beginning, you would think the book of Judges would be a description of one success after another. But Judges is not a success story because, as it turns out, the Israelites were their own worst enemies! Although Yahweh had promised the land to them, and although Yahweh was on their side as this marginalized minority fought against the mighty power structures, it turns out that there is more to success than political and military might. Success does not equate with political power or military victory. Yahweh had more in mind, and his goal was not violent overthrow, but peace (shalom) for the land of Canaan and all its inhabitants.

Yahweh wanted to change the social and political structures of the land. But this would require the Israelites’ firm allegiance to Yahweh. They would be tempted to follow the patterns of thinking and living of the Canaanites. They would be tempted to pledge their allegiance to the gods of Canaan, especially when it seemed as though those gods provided an easy way to power and pleasure. The critical battles encountered in the book of Judges are not military battles, but internal battles. The true fight the Israelites encountered was the internal struggle, a battle of the heart (leb). The chaos of Canaanite society was a result of the Canaanites not knowing Yahweh, and Israelite society would be no different unless the Israelites devoted themselves to Yahweh from the heart. The chaos in society begins in the heart, where each person is tempted to serve and worship a god other than Yahweh, or to worship no god at all. The fight is an internal fight against power-mongering, greed, and selfishness. Power, control, and pleasure are the things that will tempt Israel, and the gods of the Canaanites seemed an easy way to obtain them. That is why they must listen to the Words of Yahweh.

Why wouldn’t they listen to these Words? Why wouldn’t they follow them? Because they would rather do what is right in their own eyes. As the story of Judges unfolds, the Israelites slowly began to follow the ways of Canaanite culture, adopting the patterns of thinking and behavior that go after power, control, and pleasure. Here is the progression we see in the book of Judges:

1. The people “forgot” Yahweh and didn’t listen to him.

2. As a result, everyone did what was “right” in their own eyes instead of what was “right” in God’s eyes.

3. Because there was no truth as a standard of living, power became all important, and groups competed violently for power.

4. The result was social and political chaos, disillusionment and destruction.[4]

Yahweh had warned the Israelites that if they forget God, he would “sell them” to the Canaanites and “turn them over” to their ways. The result is what we see displayed throughout the book of Judges: violence, prejudice, civil war, abuse of women, rape, greed, and political fighting. God certainly “judges” Israel, just like he had judged the Canaanites. But the way God judges is by letting humans experience what life is like without God. As David Wells writes, “God is active in this judgment. He no longer restrains human beings in their expressions of sin, and so sin becomes, in the short run, its own judgment.”[5]

Where is God in all This?

Israel was its own worst enemy, and that nation (much like ours today) was filled with violence, greed, female abuse, racial rioting, civil war, political turmoil, economic collapse, and weeping. In the end, Israel needed to be saved from itself. Yahweh needed to “redeem” Israel from itself, to change it from within. What is God to do in this situation? If he is the Judge, shouldn’t he step in and stop all this chaos? Where is God in all this, and how does the Judge, the God who created this universe in the first place, change it, change us, so that truth, peace, and love might fill the streets instead of chaos, violence, and greed?

The word used throughout Scripture to describe where God is and how God changes us is the word redemption. To redeem something means to take something bad and turn it into something good, to turn something useless into something useful. Redemption takes time and patience. We humans are our own worst enemies, and on our own, it is tough for us to change. Each person or group has its agenda, looking out for its rights, and violence begets more violence. Do we want all this chaos, violence, abuse and greed in our societies, in ourselves? Surely not, but as Diogenes Allen said, “Evil is one of the ways we learn that we ourselves are a mystery, for we are not in full control of ourselves and cannot find any method of gaining control.”[6] We need forgiveness for ourselves and for each other to break the bondage to the past. And we need soul healing, a change in our attitudes and behaviors. We need redemption, the turning of something useless into something good. But for any redemption to occur, whether of an individual or a society, there must be one constant element: faithful love. There must be present a love that desires the best for another, a love that initiates the forgiveness and reconciliation, a love that never gives up, a love that goes to whatever lengths to help another, a love that sacrifices, a love that stoops and is near.

The word used in the Old Testament to describe this type of love is hesed, that beautiful word that perfectly describes the nature of God. The one constant throughout all of the Bible (and all of human history) is the faithfulness of God. Although the Israelites were unfaithful, God was merciful and gracious, acting to rescue them so that through them, he may be able to save a humanity that is just as chaotic as Israel. “The sovereignty or power of Israel’s God does not consist of sheer force or enforcement. If it did, God either should have been more successful in whipping Israel into shape, or God should have punished Israel incessantly. Instead, however, Israel’s God in the book of Judges and throughout the Bible simply cannot and will not be unfaithful to an unfaithful people. In short, God’s sovereignty takes the form of steadfast love.”[7] Only love can change a person or a nation, but it takes a love big enough to free us from ourselves. Love sacrifices; love forgives; love reconciles; love creates an entirely new situation.

Where is God in all our chaos today? Just like he was in Judges, he is acting to redeem us, never giving up. He is not silent; his Word remains true and still speaks through our consciences and Scripture, convicting us of the truth of his ways. As he told the ancient Israelites, God’s communication to us is not beyond our reach or far off; no, “the word is very near you; it is in your mouth and your heart so that you may obey it” (Deut. 30:14). He takes the initiative to pursue each one of us, to reconcile us, to restore the relationship, to bring life out of our death. He comes near, and his love, like an anvil, outlasts our rebellion and sin. As Cornelius Plantinga stated, “human sin is stubborn, but not as stubborn as the grace of God and not half as persistent, not half so ready to suffer to win its way.”[8] He offers a “new covenant,” one in which his own Spirit will put his Words in our minds and write them into our hearts so that we may change. He breaks the bondage to the past by saying “I will forgive their wickedness and will remember their sins no more” (Jer. 33:33,34).

But forgiveness doesn’t mean God doesn’t take evil and injustice seriously; it means he does take it seriously. He cannot and will not overlook evil; he will uphold justice because he is the Judge. But how he judges is remarkable, creative, freeing, and redeeming. He judges in a way that “makes the enemies of God his friends.”[9] God executes the judgment upon himself; he steps in and feels the pain of injustice and the whip of evil. The long-suffering love of God seen in the book of Judges finds its ultimate revelation in God “coming near” and identifying himself with his creatures in Jesus Christ, and Yahweh laid upon himself the iniquity of us all in the cross of Jesus (Isa. 53:6). As Karl Barth said, “the Judge who puts some on the left and the others on the right is in fact He who has yielded Himself to the judgment of God for me and has taken away all malediction from me. It is He who died on the Cross and rose at Easter.”[10]

How does God deal with the chaos, evil, and violence in our society? In person, upfront and in love: “God does not deal with evil impersonally by bringing the almighty force of his divine Majesty to bear directly and coercively upon it in order to reduce it to nothing. Rather does he penetrate with his holy will and living power personally into its ultimate stronghold in evil, sin and death, and absorbs its attack upon himself in order to vanquish it from within through his holy love.”[11] God takes the initiative in reconciling us to himself and each other; he is our peace that has ended the “dividing wall of hostility” that separates humans from each other (Eph 2:14). God has made a new covenant, one that is written with his own blood. The love of God is offered to all humanity, Canaanites and Israelites, Greeks and Romans, red, yellow, black, and white, we are all precious in his sight. God has pledged himself forever to humanity by the blood of his Son, Jesus Christ. God is our hero, our rescuer, our Redeemer.

[1] In the Canaanite myths, Asherah was one of numerous Canaanite gods and was married to the chief god, El. Asherah and El had 70 sons, including Baal. Worship of Asherah consisted of sexual ceremonies with the use of “fertility poles” and open sexual acts where the Canaanites tried to emulate the fertility they desired for their crops. Cult prostitution was used for these practices, which included male and female slave prostitutes.

[2] The Hebrew word translated here as “Passionate” is El Qanna, which is also sometimes translated “Jealous.” This is not a selfish jealousy, but a passionate desire for the well-being of a loved one–it is the intense love God has for humanity.

[3] Christopher J.H. Wright, The God I Don’t Understand: Reflections on Tough Questions of Faith (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 90.

[4] For a full discussion of all of these themes, see my book The Judge and the Left-Footed Leaders: Judges and Ruth for Postmodern Times.

[5] David F. Wells, Above All Earthly Powers: Christ in a Postmodern World (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004), 201.

[6] Diogenes Allen, Temptation (Cambridge: Cowley, 1986), 135.

[7] J. Clinton McCann, Judges (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2011), 25.

[8] Cornelius Plantinga, Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: A Breviary of Sin (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 199.

[9] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, IV.1, 221.

[10] Karl Barth, Dogmatics in Outline (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1959), 136.

[11] Thomas Torrance, The Christian Doctrine of God: One Being Three Persons (London: T&T Clark, 1996), 225.