I hate death. I can’t stand it. It separates us from the ones we love; it cuts short our goals and longings; it brings excruciating physical pain and waves of emotional grief. Death is a trainwreck, “the expression of a catastrophe which runs on a collision course with man’s original destination or, in other words, directly opposite of his intrinsic nature.”[1] We live with an illusion of immortality, or as one writer said, “because we cannot imagine our own death until it is thrust upon us, we live in a land where only other people die.”[2] But the illusion comes crashing down when someone we love dies suddenly or we are told, “It’s cancer.” Death suddenly becomes the trainwreck it is.

Death is that final question of our lives. We cannot avoid it because each of us will eventually die. We try to understand and resolve death, to maintain some dominion over our little worlds, but like the dark specter that confronted Ebenezer Scrooge, death confronts us with something over which we have no control, we don’t understand, we can’t resolve. Death is the question to which only something beyond death can provide the answer.

GOD HATES DEATH

Jesus felt the sting of death of someone he loved, his friend Lazarus. The story is recorded in John 11, and it is full of surprising insights into God’s answer for death. Lazarus’s sisters, Mary and Martha, have sent word to Jesus that “the one you love is sick.” Jesus is only two miles away when he got the news, so given his track record of healing people, he had plenty of time to heal Lazarus and prevent his death. But surprisingly he didn’t—he waited two days before going to Lazarus. When he finally did travel to where Lazarus was, Mary and Martha are rightfully livid: “If you had been here, my brother would not have died!” (11:21, 32). Why did Jesus wait?

The next surprise is Jesus’ reaction when he sees the sisters weeping and later when he goes to Lazarus’ grave. John 11:35, the shortest verse in the Bible, says that Jesus also “burst into tears.” Jesus wept with us in our weeping and pain. But John 11:33, and again in verse 38, adds something surprising. These verses say Jesus was “deeply moved in spirit and troubled.” The Greek word here is often used to describe the snorting of horses or of one shaking with anger. Jesus was snorting and shaking with anger! Jesus was both fighting mad about death and overcome with grief. If we want to know how God feels about death, here it is: God is angry about death—God hates death! And God himself weeps with us; he bursts into tears. God himself feels our pain, even the pain of death. But if Jesus was so angry about Lazarus’ death, why did he wait so long? If God is so angry about death and our death hurts him so much, then why in the world does God allow death in the first place?

The answers are found in the surprising things Jesus says in John 11. When Jesus finally decided to go to Lazarus, he told his disciples that Lazarus had “fallen asleep, but I am going there to wake him” (11:11). Jesus meant Lazarus had died, but he called death “sleep.” Jesus, the only one who has come back from the other side of death, says death is not final–it is like sleep. But death can only be like sleep if there is someone who can wake us from the sleep of death. Jesus also told his disciples that Lazarus’s death, and more importantly Jesus’ waking Lazarus from the sleep of death, was “for God’s glory, that God’s Son may be glorified through it” (11:4). Wait a minute—is death some cruel joke from God? He lets us experience all the cruelty of pain, suffering, and death, only to then wake us from the “sleep” of death? How in God’s name can death in any way glorify God? If God is in control of life and death, then why is there death at all?

SO WHY DEATH?

The Bible addresses the question of death by saying it, too, can be understood through the lens of God’s love for us. God’s love goes all the way back to that first, seminal story about humans in the Bible, the story of Adam and Eve in the garden of paradise. As you recall, there were two trees of special importance in this paradise: the tree of knowledge of good and evil, and the tree of life. From the story, we learn that humans were not created as immortal creatures; rather, immortality is a gift from God. It was only if they ate from the “tree of life” that they could “live forever” (Gen. 3:22). We are not immortal; we are limited creatures, and we get all of life from the Source outside ourselves. But that is what haunts us and gnaws at us—how can we transcend our finiteness, how can we become our own god?

That is where the other tree in the garden comes in–the “tree of knowledge of good and evil.” God had told them they could eat from any tree in the garden, but he warned them that if they ate from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, they would “surely die” (Gen. 2:17) (which, by the way, is the first promise of the Bible). What is this “tree of knowledge of good and evil,” and why is eating from it the reason for death? The tree of knowledge of good and evil represents the decision that every one of us makes in life: do we trust God or trust ourselves? The temptation in the garden, which is the temptation of everyone, is to try on our own to “break and transcend the limits which God has set” for us. As Reinhold Niebuhr writes, humanity “does not recognize the contingent and dependent character of its life and believes itself to be the author of its own existence, the judge of its own values and the master of its own destiny.”[3]

So why did the Creator cast them out of paradise? Maybe the answer is best explained in this question: would you like for Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin to live forever? The whole history of humanity reveals that when we turn ourselves from the very source of Love, Joy, and Life, the result is what we see played out every day, a world in which we seek to become our own gods at the expense and pain of everyone around us. Would we want this type of suffering to go on forever? As Ted Peters writes, “It is out of love, then, that God separates Adam and Eve from the tree of life. Death is a gift of divine grace because it marks the point at which the consequences for sin come to an end. There is no suffering in the grave. Death is the door that God slams shut on evil and suffering in his creation.”[4]

But death would only be divine grace if death were not the end. Could there be a way that humanity could not only understand and accept its dependence on God, but actually come to trust God? And trust God because we come to realize through God’s actions for us that God is completely trustworthy, full of compassionate love and tender mercy? Could and would God provide a way for us to become more like him, reflecting his loving heart, and at last eat from that tree of life and live forever?

I AM THE WAY

God is completely trustworthy, and he has provided a way. God will not let death have the final word—God has the final word. How he has provided the way is the final surprising twist in what Jesus says in John 11. When Jesus finally goes to Lazarus, Mary comes out to meet him and angrily chides him, “If you had only come sooner!” (11:21). Jesus tells her, “Your brother will rise again.” Martha trusts God; she believes that the God who gave her brother life in the first place is the God of hesed, of unconditional love, and so she says, “I know he will rise again at the last day” (11:24). But what Jesus says next is the most surprising thing in this whole episode. Jesus says, “I AM the resurrection and the life. He who believes in me will live, even though he dies. And whoever lives and believes in me will never die” (11:25).

Jesus intentionally used the same phrase to describe Yahweh in the Old Testament (I AM) to emphasize that God had come down into our grief and wilderness. But God is bringing with him resurrection, the defeat of death itself. That final, future defeat of all death for everyone has come from the future into the present in Jesus. Jesus is saying that the “last day” has arrived ahead of time, in Jesus and in his resurrection.

Instead of waiting until we die to meet our Maker (which we surely will), our Maker comes to meet us now, in this life. God has come to meet us now, before we die, not only to assure us that death is like sleep and he will certainly wake us, but so that the new life, the good life of God’s future, might start taking place in our lives now! “It isn’t a matter of waiting until God eventually does something different at the end of time. God has brought his future, his putting-the world-to rights future, into the present in Jesus of Nazareth, and he wants that future to be implicated more and more in the present.”[5]

God has come in the middle of history so that all his beloved humans might be freed from slavery to the fear of death and learn to live in the trusting relationship of love we were created for. Or, in other words, to live like Jesus. The future, our final triumph over death, has come into the present so that we can live full, flourishing lives now in anticipation of the future. “Our trust is in the God of the future who is present now. Divine love ties us to the ultimate future and gives us the security we need; that love has been liberated within our souls by the power of the gospel to create new life amid the present aeon of death.”[6]

TAKE OFF THOSE GRAVE CLOTHES!

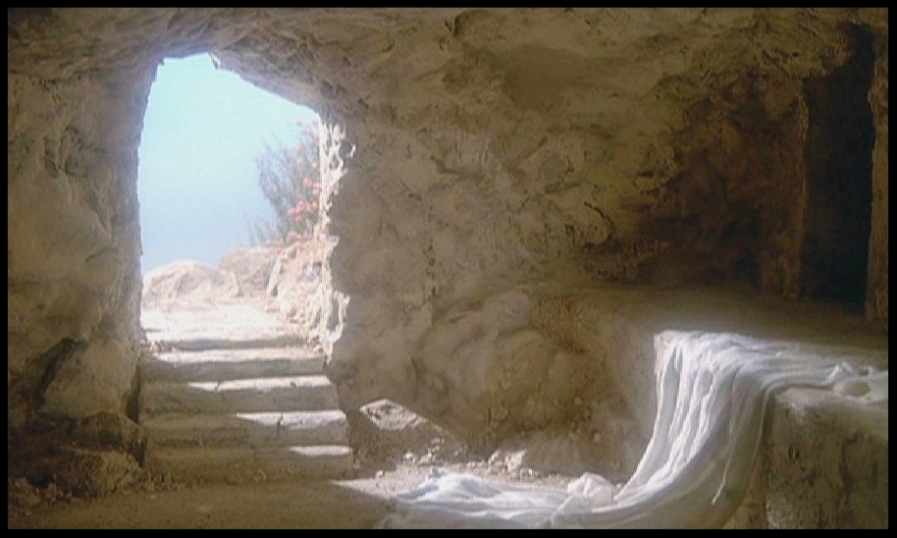

When Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, he asked for the stone to be rolled away. He then looked up to heaven, gave thanks to the restful Father and called Lazarus back to life. When Lazarus came out from the tomb alive, Jesus said, “Take off those grave clothes and let him go” (11:46). That is the word that Jesus, the Risen One, speaks to each of us: take off the grave clothes of fear, anxiety, hate, bitterness, and death, and come to meet the Living God!

God doesn’t say “No!” to his creatures; his answer to us is “Yes!” and all of God’s promises find their fulfillment in God’s final “Yes!” in Jesus (2 Cor. 1:20). God is for us, he has set his seal of ownership and protection over us and put his Spirit in our hearts as a deposit, guaranteeing what is to come (2 Cor. 1:22). God doesn’t want you to wait until you die to meet your Maker (which you will), but he is dying to meet you now so that you can begin to experience the life to come.

[1] Helmut Thielicke, Death and Life (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1970), 105.

[2] Christian Wiman, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014), 56.

[3] Reinhold Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man, 2 Vols. (New York: Scribner’s, 1941), 1:179, 180, 181.

[4] Ted Peters, God—The World’s Future (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2000), 322.

[5] N.T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church (New York: HarperOne, 2008), 215.

[6] Peters, God—The World’s Future, 375.